What effects have Trump’s Tariffs had on employment, prices, and production output in the manufacturing sector of the US?

IB Extended Essay in Economics

Introduction

In 2016, Donald Trump, against the predictions of many political commentators and national polls, won the presidential election. One of the major reasons behind his win was how well he appealed to blue-collar workers in Rust Belt states such as Iowa, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania, all of which had previously gone to Democrats for at least the previous two elections. The main driver behind this was Trump’s rhetoric in regard to trade and its relation to manufacturing. He paints a narrative of globalization and multilateral trade agreements causing a decline in the wealth and manufacturing of the United States of America, and he claims that he will be able to “bring back” those jobs and wealth to the US. Trump’s main policies in regards to trade came in 2018 when he passed a series of tariffs on solar panels, washing machines, steel, and aluminum, in addition to pulling out from various trade agreements such as the TPP. He has rationalized implementing tariffs by saying that "If companies don't want to pay Tariffs, build in the U.S.A. Otherwise, let's just make our Country richer than ever before (through the tax revenue from the tariffs)!" Here he states that the tariffs will either bring back US manufacturing or make the US “richer than ever before”. A massive body of research supports the consensus that the tariffs have hurt US wealth, not contributed to it. A quote from the Congressional Budget Office encapsulates this effectively; “Tariffs are expected to reduce the level of real GDP by roughly 0.5 percent and raise consumer prices by 0.5 percent in 2020. As a result, tariffs are also projected to reduce average real household income by $1,277 (in 2019 dollars) in 2020”. The tariffs are evidently not making the US richer, and in this essay, I will evaluate whether or not the other half of Trump’s dichotomy follows.

In order to do this, I will be answering the following question: What effects have Trump’s Tariffs had on employment, prices, and production output in the manufacturing sector of the US? I will be considering the January 2018 tariffs on solar panels and washing machines as well as the March 2018 tariffs on aluminum and steel. My hypothesis is that, given how import tariffs typically work, this may benefit a handful of American industries who produce the tariffed goods domestically, however, it will harm far more American manufacturers than it will help.

If this is true, then these tariffs may have a wide range of harmful effects on the American economy. Beyond the immediate negative consequences to those manufacturers, manufacturing as an industry has a wide range of downstream effects on other aspects of the economy. For example, should core products, which are often manufactured, be subject to increased prices, the relatively inelastic demand of those products would lead to less disposable income for the average family. This would lead to other, more luxury industries suffering effects since the aggregate demand for their products will fall in tandem with a drop in disposable income. Furthermore, a fall in output for manufacturing may cause a shortage of these core products.

With all these in mind, it is important to empirically understand the effects of these tariffs, especially given as Trump’s tariffs are one of the largest protectionist policies put forward in modern economic history. This would serve as an important case study to other nations and politicians in regards to what the potential effects of tariffs are on the domestic economy, and would therefore most likely play a role in the drafting of trade policy going forward.

Methodology

For the purpose of this essay, I will be focusing on the effects of these tariffs on the manufacturing sector of the United States. Employment, output, and prices of the manufacturing sector being the main metrics by which I will measure the effects. I will also be looking at more of a theoretical understanding and deductive analysis of why these results are as they are, which will touch on a wide range of economic concepts including International Trade and Free trade vs Protectionist policy.

In order to obtain empirical results on the effects of the tariffs, I have utilized highly credible academic literature on the topic in order to obtain relevant information. The main resource is a study authored by Aaron Flaaen and Justin Pierce, the Senior and Principal Economists respectively for the US Federal Reserve. The study was published in December of 2019 and is written with the purpose of “Disentangling the Effects of the 2018-2019 Tariffs on a Globally Connected U.S. Manufacturing Sector”. This is a highly reliable source for a range of reasons. Firstly it was published by the Federal Reserve, which is the United States federal banking system, which boosts their credibility. Furthermore, the two authors of the study are high ranking economists of the Federal Reserve, both of them holding Ph.D. degrees in Economics. Finally, the study was published in December of 2019, which was not very long ago, hence increasing the likelihood that all information is up to date. In addition to this study, I will also be basing a part of my analysis on a paper published by “The Trade Partnership”. The Trade Partnership is an international trade and economic consulting firm and the particular paper I am focusing on has been picked up on by large publications such as Quartz. The authors of the paper, once again, have degrees in the field of economics, with one of them, Dr. Joseph Francois, even being a professor of economics in addition to having worked as the acting director of the Office of Economics at the U.S. International Trade Commission.

In addition to these two academic works, I will also be using an academic poll conducted by The University of Chicago. It was done in tandem with the IGM Economic Experts panel and polled a wide range of economists from multiple different universities.

Finally, in regard to the theoretical parts of this essay, I have utilized the IB Economics Second Edition course companion in order to be able to properly analyze the concepts of international trade and Free Trade vs Protectionist trade policy. In general, the theory suggests that free trade leads to a whole host of positive economic effects such as lower prices, greater choice, more efficient allocation of resources, etc. However, there are still some valid arguments for protectionism such as protecting domestic industries, which was the stated reason for implementing the tariffs. Tariffs, Ceteris Paribus, tend to increase government revenue, increase domestic revenue and market share, and decrease foreign revenue and market share. However, not without a dead-weight loss of welfare. With this theory in mind, I will analyze exactly how the theory explains the main findings, and weigh them in relation to the research question of this essay.

Main Findings

The studies come to a rather conclusive, unambiguous conclusion. Tariffs have hurt the manufacturing sector of the United States. The US Federal Reserve study has identified 3 key effects of the tariffs and measured their impact on the manufacturing sector. Effect 1 is a positive one; the effect of US import tariffs causing domestic companies to turn to US-based manufacturers as a replacement for obtaining the tariffed goods. This is measured by the share of domestic absorption affected by the tariffs. Effect 2 a negative one; the effect that the tariffs have on the price of intermediate inputs (goods needed to produce a product) that causes an increase in price which in turn hurts US manufacturers’ competitiveness in both international and domestic markets. This is measured by the share of industry costs caused by the tariffs. Effect 3 is another negative one; the effect of retaliatory tariffs placed on US goods by US trading partners, which causes the US to be at a disadvantage in comparison to other producers. This is measured by the share of industrial export US trading partners as caused by the tariffs. These measures are then correlated to monthly data on prices, employment, and outputs of the manufacturing sector. Of course, the study also adjusts for a wide range of confounding variables such as pre-trends, differences in exposure to the tariffs, performance at different points in the business cycle, and aggregate shocks to ensure that the results are causative and not just correlative.

The study then measures the empirical consequences of the one positive effect of tariffs on manufacturing in comparison to the two negatives ones to see if the effects were overall positive or negative. They find that “tariff increases enacted in 2018 are associated with relative reductions in manufacturing employment and relative increases in producer prices.” The fall in employment was caused by the increase in production costs and retaliatory tariffs (effects two and three). While the import protection (effect one) did to some extent counteract this, it was dwarfed in comparison to the others when it came to the empirical outcome. The rising prices were solely caused by the increase in production costs and had no counteracting effects. There was little evidence that the tariffs had any effect on industrial production, despite the price increases.

Numerically it was found that shifting exposure to the tariffs from the 25th to the 75th percentile caused a reduction of 1.4% in manufacturing employment. The 3 effects stood for +0.3, -1.1, and -0.7 percent of the change respectively. An interquartile shift in exposure to tariffs also causes a 4.1% increase in prices. This was entirely caused by effect 2.

Through cross-referencing with another study we can get a more in-depth understanding of exactly what manufacturing industries are hurt by the tariffs.

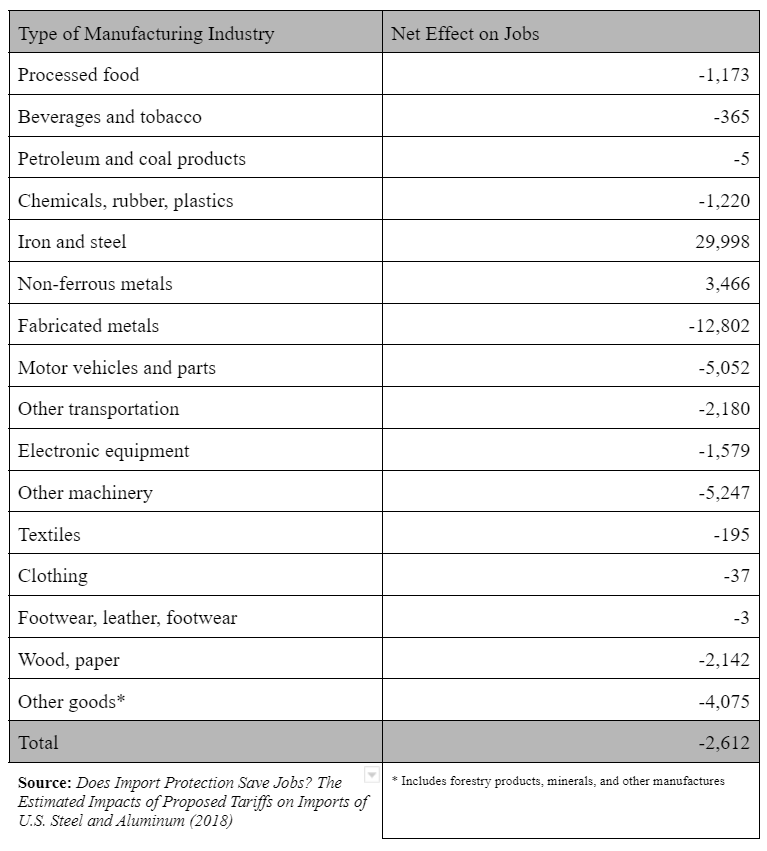

The Trade Partnership study gives us a more detailed understanding of exactly where the US is gaining and losing jobs. They utilize a class of economic models known as “Computable General Equilibrium” or “CGE” models. This is the same type of economic model used by, for example, the United States Department of Commerce when analyzing the effects of tariffs.

They found that the steel and aluminum tariffs would gain the domestic iron and steel industries 29,998 jobs and the non-ferrous metal industries 3,466 jobs for a total of 33,464 jobs gained in the manufacturing sector. However, other manufacturing industries are hurt by the tariffs, and those losses exceed the gains. Manufacturing would also lose 36,076 jobs, causing a net loss of 2,612 in the US manufacturing sector. Among the manufacturing industries hardest hit by the tariffs are fabricated metals (-12,800), motor vehicles and parts (-5,052), and other transportation equipment (-2,180). There are also devastating effects on jobs in non-manufacturing sectors, totaling a total net loss of 145,870 jobs in the overall US economy, however, this is beside the focal point of this essay. There are two limitations of this study, as opposed to the Federal Reserve study this one does not take into account Effect 3, retaliatory tariffs, which are tariffs put in place by other nations to compensate for the loss of market share on the US market. Due to this factor, these numbers are low-end estimates, the real amount of lost jobs are far greater. In addition to this, this study only considers the tariffs on steel and aluminum, not those on washing machines and solar panels. Nevertheless, the study is still useful in getting some sort of idea of exactly what industries are gaining due to effect 1 and which are suffering due to effect 2.

Analysis and Discussion

The trade tariffs were a disaster for the manufacturing sector of the United States. They have caused a rise in producer prices, a fall in employment, and no increase in production output, despite these raised prices. However, this was hardly unexpected. An academic poll conducted by the University of Chicago presented 43 Economists from a wide range of prestigious universities with the following statement; “Imposing new US tariffs on steel and aluminum will improve Americans’ welfare”.

The economists were then prompted to express to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the statement, as well as to provide a measure of how confident they were in their answer from a scale of 1-10, one being the lowest, ten being the highest. The results were unanimous, a vast majority (65%) of the 43 economists who were asked strongly disagreed with the statement, in addition to the 28% who just answered disagree. The missing 7 percent is due to the fact that 3 economists did not answer the question. Not one economist was uncertain or agreed in any capacity. When the answers were weighted by the confidence expressed the results were even more pronounced, with 76% strongly disagreeing and 24% just disagreeing.

The economists were also given the option to provide a comment in addition to their answers, many of which correctly predicted exactly why this would be the case. Larry Samuelson from Yale, who strongly disagrees with a confidence measure of 10 states that “A small number of people, engaged in steel and aluminum production, will benefit from these tariffs, at great cost to many others.” They were by no means the only economist to provide this analysis in his comment, however in my opinion he encapsulated it most effectively.

In this section, I will be going over what economic theory and concepts these economists may have used in order to accurately predict the outcomes of the trade tariffs. The most important one is the theoretical understanding of what effects tariffs generally have on an economy. This can be expressed most poignantly through a tariff diagram.

This diagram illustrates the effect of the tariffs on the US steel industry. Before the tariffs come into play Q2 amounts of steel were being used at the price of P (world). US domestic production stood for Q1, and imports for everything in between Q1 and Q2. As the tariffs are imposed Supply and P (world) shifts upwards into Supply and P (world) + the 20% tariff on steel. This will reduce demand (since prices have increased) from Q2 to Q4. It also causes US domestic production of steel to rise, since importing it is now more expensive. As US domestic production increases from Q1 to Q3 so does its revenue. US domestic revenue used to be just g it is now a+b+c+g+h. Foreign production now only stands for Q3 to Q4. The US government now gets d+e as tax revenue from the tariffs. Due to this and the fact that the overall demand for imported goods has fallen, foreign producer revenue falls from h+i+j+k to just i+j.

Due to this, US domestic steel production has increased, however, at the cost of becoming a more expensive product. For other US manufacturers who need steel as an intermediate input, the higher pricing falls on them to pay for. As the Trade Partnership study suggests, the hardest hit of these industries are likely to be fabricated metals, motor vehicles and parts, and other transportation equipment. This will cause these and many other industries’ production to become more expensive, thus causing them to either increase pricing, cut other production costs, or both. This reduces their competitiveness, both domestically and internationally. Furthermore, there is also a loss of consumer surplus from Q4 to Q2, as there were consumers who are not prepared to pay the new, elevated price of steel. This is a deadweight loss of welfare. Tariffs also cause another type of deadweight loss of welfare in the form of a loss of world efficiency, but this is beside the focal point of this essay.

In addition to this, there are also the retaliatory tariffs placed on imported US products. In that situation, it is US industries that go from generating revenue of h+i+j+k to just i+j in foreign markets.

Since jobs in US industries that use steel in their production outnumber jobs that are involved in the production of steel around 80 to 1, it is not hard to understand why a positive to steel-producing industries at the cost of steel-using industries would most likely end up being an overall negative. This is the exact outcome that we see demonstrated in the results of the studies. The increased employment in steel-producing industries (effect 1) is overshadowed by the loss of jobs in steel-using industries due to the reduction in competitiveness and efficiency (effect 2) and the loss of jobs at the hand of retaliatory tariffs hurting US presence in foreign markets (effect 3). The higher prices also cost the US economy in a wide variety of other ways, and despite the prices of manufactured goods going up, production output has not gone up with it.

Conclusion

What effects have Trump’s Tariffs had on employment, prices, and production output in the manufacturing sector of the US? According to available information on the topic, the 2018 tariffs on solar panels, washing machines, steel, and aluminum have had an empirically negative effect on the US, not least in the very sector they were meant to help, manufacturing. Through the net effect of the 3 major effects of tariffs, the US manufacturing sector has seen a 1.4% employment reduction, be forced to increase prices by 4.1%, and has seen no increase in production output. The major casualties are industries that use the tariffed goods in production or for resale, and this rings true for the broader effects of the tariffs as well. They are projected to reduce the level of real GDP by around 0.5% as well as rising consumer prices by 0.5% in 2020. Furthermore, they are projected to reduce the average real household income by $1,277 (2019 dollars) in 2020. This is all in addition to the lower end estimate of 145,870 jobs lost in the economy overall and general reductions in wages due to the need to cut production costs.

There are some limitations to these estimates, while this study has measured the domestic effect of the tariffs, especially on manufacturing, it does not take into account the potential for the tariffs to serve as, in the words of MIT economist David Autor, “a strategic gambit in a longer game that deters abuse of free trade agreements”. In addition to this, there is also the fact that estimates on which manufacturing industries see exactly how much of a change in employment is slightly speculative, as the study I based my analysis on did not account for retaliatory tariffs in their methodology.

Nevertheless, they do serve as a safe lower-end estimate, and it is precisely and exclusively for that purpose, and in that way that I have used those findings.

Bibliography

Montanaro, Domenico. “7 Reasons Donald Trump Won The Presidential Election.” NPR, NPR, 12 Nov. 2016, www.npr.org/2016/11/12/501848636/7-reasons-donald-trump-won-the-presidential-election?t=1598875950244.

“Iowa Presidential Election Voting History.” 270toWin.Com, www.270towin.com/states/Iowa.

“Ohio Presidential Election Voting History.” 270toWin.Com, www.270towin.com/states/Ohio.

“Wisconsin Presidential Election Voting History.” 270toWin.Com, www.270towin.com/states/Wisconsin.

“Pennsylvania Presidential Election Voting History.” 270toWin.Com, www.270towin.com/states/Pennsylvania.

“Full Transcript: Donald Trump's Jobs Plan Speech.” POLITICO, 28 June 2016, www.politico.com/story/2016/06/full-transcript-trump-job-plan-speech-224891.

Gonzales, Richard. “Trump Slaps Tariffs On Imported Solar Panels And Washing Machines.” NPR, NPR, 23 Jan. 2018, www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/01/22/579848409/trump-slaps-tariffs-on-imported-solar-panels-and-washing-machines.

Horsley, Scott. “Trump Formally Orders Tariffs On Steel, Aluminum Imports.” NPR, NPR, 8 Mar. 2018, www.npr.org/2018/03/08/591744195/trump-expected-to-formally-order-tariffs-on-steel-aluminum-imports.

“The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2020 to 2030.” Congressional Budget Office, Congressional Budget Office, www.cbo.gov/publication/56073.

Flaaen, Aaron, and Justin Pierce (2019). “Disentangling the Effects of the 2018-2019 Tariffs on a Globally Connected U.S. Manufacturing Sector,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2019-086. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2019.086.

“Does Import Protection Save Jobs? The Estimated Impacts of Proposed Tariffs on Imports of U.S. Steel and Aluminum (2018).” TRADE PARTNERSHIP WORLDWIDE, LLC, 15 Mar. 2018, tradepartnership.com/reports/does-import-protection-save-jobs-the-estimated-impacts-of-proposed-tariffs-on-imports-of-u-s-steel-and-aluminum-2018/.

Timmons, Heather. “Five US Jobs Will Be Lost for Every New One Created by Trump's Steel Tariffs.” Quartz, Quartz, 5 Mar. 2018, qz.com/1221912/trump-tariffs-five-us-jobs-will-be-lost-for-every-new-one-created-by-trumps-steel-tariffs/.

“Steel and Aluminum Tariffs.” Igmchicago.org, IGM Economic Experts Panel, 2018, www.igmchicago.org/surveys/steel-and-aluminum-tariffs/.

Flaaen, Aaron, and Justin Pierce (2019). “Disentangling the Effects of the 2018-2019 Tariffs on a Globally Connected U.S. Manufacturing Sector,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2019-086. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2019.086.

“Does Import Protection Save Jobs? The Estimated Impacts of Proposed Tariffs on Imports of U.S. Steel and Aluminum (2018).” TRADE PARTNERSHIP WORLDWIDE, LLC, 15 Mar. 2018, tradepartnership.com/reports/does-import-protection-save-jobs-the-estimated-impacts-of-proposed-tariffs-on-imports-of-u-s-steel-and-aluminum-2018/.

“Steel and Aluminum Tariffs.” Igmchicago.org, IGM Economic Experts Panel, 2018, www.igmchicago.org/surveys/steel-and-aluminum-tariffs/.

Russ, Lydia Cox and Kadee, et al. “Will Steel Tariffs Put U.S. Jobs at Risk?” Econofact, 1 Nov. 2018, econofact.org/will-steel-tariffs-put-u-s-jobs-at-risk.

“Steel and Aluminum Tariffs.” Igmchicago.org, IGM Economic Experts Panel, 2018, www.igmchicago.org/surveys/steel-and-aluminum-tariffs/.